(Answering the question “Why does DAS do what it does?”)

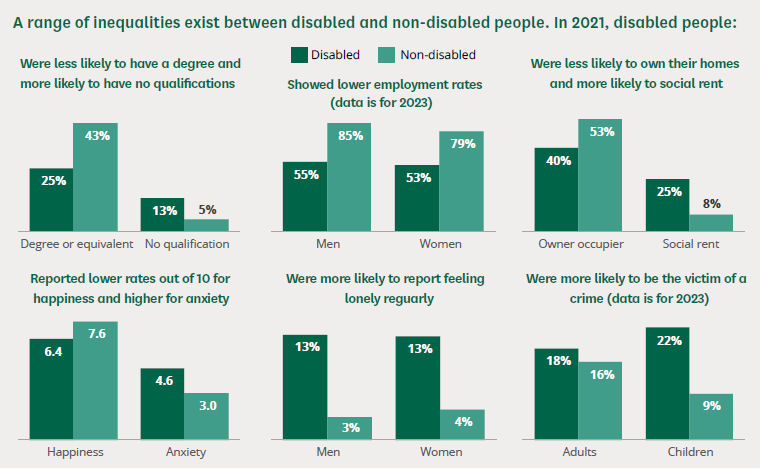

The disabled face inequality on many fronts as illustrated in this chart from the “UK disability statistics: Prevalence and life experiences” available from the House of Commons library

On this page you can read about the following (scroll down for the full story):

Extent of Disability in the UK: View the latest available government statistics from the last DWP Family Resources Survey on the extent of disability in the UK: the numbers: by age, by impairment type and by region. In 2021 to 2022, 24% of people were disabled with a higher proportion of females (26%) than males (22%).

“Hunger in the UK”, a Trussell Trust report: This states that 75% of people referred to food banks in their network say that they or a member of their household are disabled (when only 23% of working-age adults are registered as disabled in the government’s Family Resources Survey (see below)).

EHRC update report to UN says 7 years later the government still failing the disabled: The latest commentary from the Equality and Human Rights Commission, reported by the BBC here in August 2023, assessed the extent to which UN recommendations made in 2016 (entitled “Being disabled in Britain – A journey less equal”) have been implemented. It said, despite limited progress in certain areas, “we are disappointed to see no progress against some other recommendations”. They found there had been no progress in monitoring the impact of welfare reforms or access to justice for disabled people. It said there continued to be a disproportionate number of disabled people living on low incomes or in poverty with some facing long waits for decisions on eligibility for benefits. This is something badly affecting DAS clients on a daily basis and the delays have lengthened on PIP applications to over six months.

Massive gap in income causing further deprivation for the disabled: Research from the Resolution Foundation reported by the Guardian in January 2023 highlighted “massive income gaps amid the cost of living squeeze” causing a disproportionate impact on the disabled as they struggle to heat their homes and cut back on food during the winter. People with disabilities have an available amount to spend 44% lower than that of other working-age adults, exposing them hugely to the rising cost of essentials.

The Disability Price Tag: Cost of living higher: disabled households with at least 1 disabled adult or child, face extra costs of £975 a month on average; and for households with 2 disabled adults and at least 2 children, these average extra costs increase to £1,248 a month.

The disability employment gap: Only 54% of working age-disabled people in the UK are in work compared to 82% for working-age non-disabled people – meaning there is an employment gap of 28%. Working-age people with learning disabilities have an employment rate of just 6% despite the fact that 65% wanting to work. The DWP claims that more disabled people can, and should, be in work because of the increased availability of homeworking since the pandemic. However, Mind research showed a drop in such job roles since the pandemic – with 84% of 2,000 recruiters reporting they had seen a reduction since the pandemic ended.

Giant health assessment firms paid £millions but not meeting targets: Campaigning magazine Private Eye reported in January 2023 that DWP’s own audits highlight shortfalls in properly assessing disabled people’s applications for ESA, PIP and UC.

Damaging effect of the 2022 rise in the cost of living: In March 2022 ITV News reported that families looking after those who are disabled were increasingly worried about being able to pay their bills as the cost of living soared. As essential services and goods like heating, travel, equipment and therapies became more expensive, families living with less and less were being forced to go without essential items.

Flaws in the DWP system led to almost 80,000 PIP decisions being overturned at initial review: Read the Independent article from February 2022 in which the Department of Work & Pensions admitted it had wrongly refused disabled people benefits at a record rate as the cost of needless reviews to taxpayers soared.

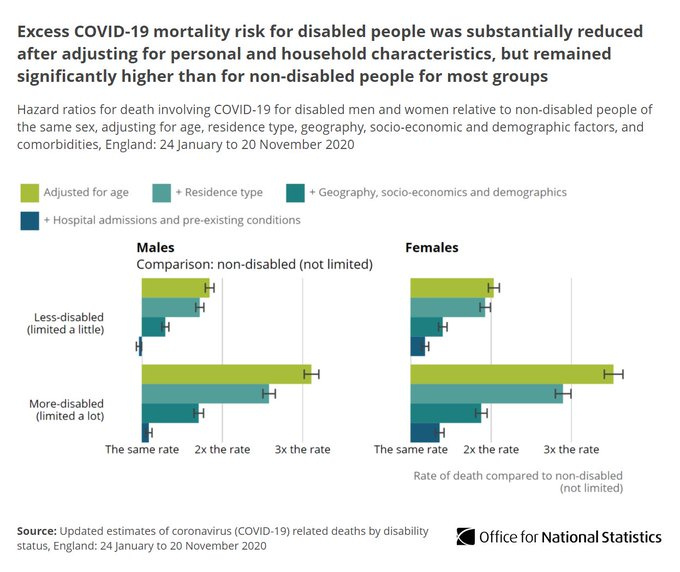

Impact of the Pandemic: See the stark reality of how the pandemic disproportionately affected the disabled including a report from the Office for National Statistics (ONS) that shows the risk of death was more than 3 times greater for the more-disabled compared with non-disabled.

Homelessness: The number of ill and disabled people becoming homeless surged by 53% in 2019 as local councils found themslelves increasingly unable to provide them with support. Read more here.

Poverty and Social Exclusion: Review the report by the New Policy Institute Monitoring Poverty and Social Exclusion which found that “once account is taken of the higher costs faced by those who are disabled, half of people living in poverty are either themselves disabled or are living with a disabled person in their household.”

UN Convention on the Rights of Disabled People – Government Civil Society Shadow Report: This report was led by Inclusion London in March 2022 and comments on how well the government is doing to implement the Convention. One key finding was that the pandemic response discriminated against disabled people and violated their equal right to life.

Suicide Prevention: Find out about the causal link between disability, financial hardship and the likelihood of attempted suicide. Shocking numbers of people have committed suicide closely related to a refusal or downgrading of their benefits following assessment by DWP contractors. Read about the impact our work has in preventing suicide and self-harm.

Welfare Reform Injustice and Waste: ITV News reports that a freedom of information data has revealed that £440M has been substantially wasted since 2013 fighting disabled people who decided to appeal after being turned down for two key benefits. The welfare reforms were designed to reduce the cost of disability benefits and have failed. It represents such poor value for money to us the tax payer and its getting worse. On average 75% of appeals (100% throughout 2020 and 2021 for DAS) are lost by the Department of Work & Pensions but the impact on disabled people from forcing them to fight in the courts can be devastating, pushing some into poverty and increasing levels of stress and anxiety.

Disabled benefit claimants unable to afford food: Read a Daily Mirror story about the DWP’s refusal to publish a report that admits its applicants are often unable to meet essential day-to-day living needs, such as heating their house or buying food.

Domestic Abuse: Access the Safe Lives research on Disabled People and Domestic Abuse that found the disabled are more than twice as likely to experience some form of domestic abuse than non-disabled victims and that they also suffer more severe and frequent abuse over longer periods of time.

Rural East Suffolk is an Area of Relative Deprivation: See the relatively high levels of deprivation that exist respectively in the urban environment of Ipswich and the rural towns and villages of East Suffolk as analysed by Public Health Suffolk.

The Social Model: Read about the Social Model of disability to try and understand the disabled persons perspective. It is thought provoking.

Latest government statistics on the extent of disability in the UK

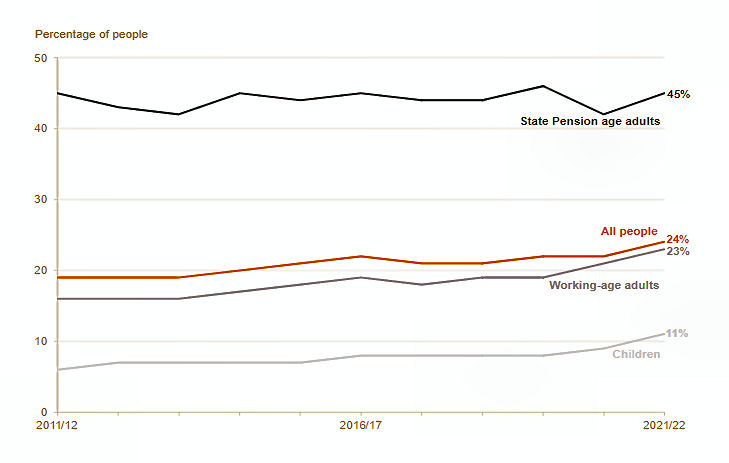

According to the latest Department for Work & Pensions’ Family Resources Survey published for the year ending 2022, 16.0 million people (24%) reported a disability people in the UK, which is an increase of 3.9m since 2011-2012. However, the UK population has grown over that time so population growth alone accounts for some of the increase.

[NB: A person is considered to have a disability if they report a long-standing illness, disability or impairment which causes substantial difficulty with day-to-day activities (the core definition of disability stated in the Equality Act 2010)].

16.0 million people

24% of the population

Sharp rise up from 22% last time and from 19% ten years ago, with a higher proportion of females (26%) than males (22%)

Not surprisingly, the proportion of disabled people increases with age:

Children 11%

Working age adults 23%

Over state pension age 45%

Since 2012:

- Females (all ages) increased from 19% (6.1m) to 24% (7.8m) and males from 18% (5.3m) to 19% (6.3m).

- Children increased steeply to 11% (6% a decade ago). School-age children receiving disability benefits, mainly disability living allowance, rose from 2-3% in 2002 to 5-7% in 2022. This is largely accounted for by increases in claims for learning disabilities, behavioural disorders and ADHD.

- Working-age adults have increased to 23% (from 19%). Nil Guzelgun, policy and campaigns manager for mental health charity Mind, said the pandemic and cost-of-living crisis had both contributed to a rise in young people struggling to cope.

- For pension age, the number has fluctuated up and down in the range 42-45% for the past decade.

“Hunger in the UK”, a Trussell Trust report says 75% of users are disabled or have a disabled family member

According to the Trussell Trust report “Hunger in the UK” in August 2023 (in which the word “disability” occurs 56 times), 7% of UK households accessed support from an ecosystem of food aid across the UK, such as receiving support from a food bank or accessing low-cost food aid from a social supermarket. This means an estimated 5.7m people were supported by food aid in the UK.

Despite the growth in the number of food parcels (in the five years between 2017/18 and 2022/23, the number of emergency food parcels more than doubled). However, the research showed that more than two thirds of those experiencing food insecurity have not received food aid. Food bank use therefore does not represent the entirety of need across the country and many others appear to be facing serious hardship without such help.

According to the report, the impact has been especially severe for some parts of society:

“Some groups are significantly overrepresented in the proportions experiencing food insecurity and needing to use food banks (including): more than half of households experiencing food insecurity, and three quarters of people referred to food banks in the Trussell Trust network say that they or a member of their household are disabled.”

Paid work is not providing the reliable route out of hardship you might expect. One in five people referred to food banks are in working households, with insecure work particularly correlated with food insecurity. Other people would like to work but find that jobs are inaccessible, especially for disabled people, people with caring responsibilities, and people – especially women – with children. While insecure finances are the primary cause of food bank use, this research shows that wider factors such as adverse life events and social isolation exacerbate the impacts of insufficient income, leaving some people more likely to have to access food banks.

There is significant evidence about the complex and cyclical relationship between poverty and disability/ill-health. Long-term health conditions are more prevalent amongst households with lower levels of income, and conditions tend to be more severe. Meanwhile, Marmot’s social gradient demonstrates how low income in turn leads to worse health outcomes, creating a vicious cycle of outcomes. The report’s data demonstrated how disability and ill-health significantly increase a person’s likelihood of being food insecure and of having to rely on food banks.

EHRC report to UN says government still failing the disabled

In a report commented on by the BBC in August 2023, the Equality and Human Rights Commission updated its assessment of the extent to which UN recommendations made 7 years ago in 2016 have been implemented. It accused the UK Government of making “slow progress” in improving the lives of disabled people.

In a new report submitted to the UN, the EHRC warns that many disabled people continue to face discrimination in the UK, and the situation continues to worsen, particularly in light of current cost-of-living pressures. The report assesses the extent to which the previous UN recommendations from 2016 have been implemented. It said, despite limited progress in certain areas, “we are disappointed to see no progress against some other recommendations”.

“While commitments to address some issues have been made, actions have been delayed or don’t go far enough,” the human rights watchdog said. The report found there had been no progress in monitoring the impact of welfare reforms or access to justice for disabled people. Its report also found gaps in “meaningful engagement” between governments and disabled people across many parts of the UK.

It said there continued to be a disproportionate number of disabled people living on low incomes or in poverty with some facing long waits for decisions on eligibility for benefits. Kishwer Falkner, chairwoman of the EHRC, urged the UK and Welsh governments “to address the problems faced by disabled people and take action to address the UN’s recommendations from 2016”. “Disabled people must be treated with dignity, respect and fairness,” Ms Falkner said. “The recommendations made years ago must be addressed if the lives of disabled people are to improve.”

The delays in the welfare systen badly affect DAS clients on a daily basis and the delays have lengthened on PIP applications to over six months.

The Disability Price Tag: Cost of living higher

In its latest research for 2023 the Scope charity relooked at the extra costs faced by disabled households and found that:

- disabled households with at least 1 disabled adult or child, face extra costs of £975 a month on average

- for households with 2 disabled adults and at least 2 children, these average extra costs increase to £1,248 a month

- disability related extra costs are equivalent to 63% of a disabled household’s income, after housing costs

- disabled people often face higher costs for their gas and electricity, many saying they need more heating to stay warm, and yet others that they need to use extra electricity to charge up items of assistive technology.

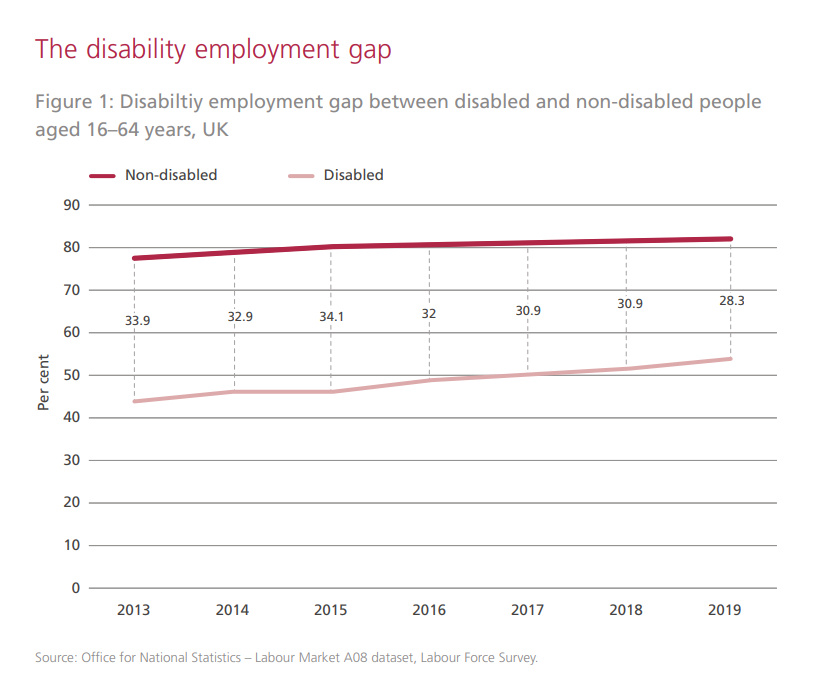

The disability employment gap

According to research published by the Centre for Social Justice there are 7.7 million working age-disabled people in the UK today, of whom 53.6 per cent (4.1 million) are in work. This compares to an employment rate of 81.9 per cent for working-age non-disabled people – meaning there is an employment gap of 28.2 per cent.

For certain health types, the numbers are even more concerning. Working-age people with learning disabilities in England have an employment rate of just 5.9 per cent. This is despite the fact that 65 per cent of people with learning disabilities want to work.

The DWP in 2023 claimed the benefits system does not reflect changes to the job market, asserting that more disabled people can, and should, be in work because of the increased availability of remote jobs since the pandemic. However, Mind research carried out with 2,000 recruiters revealed a drop in home-based roles since the pandemic – with 84% of recruiters reporting they had seen a reduction since the pandemic ended.

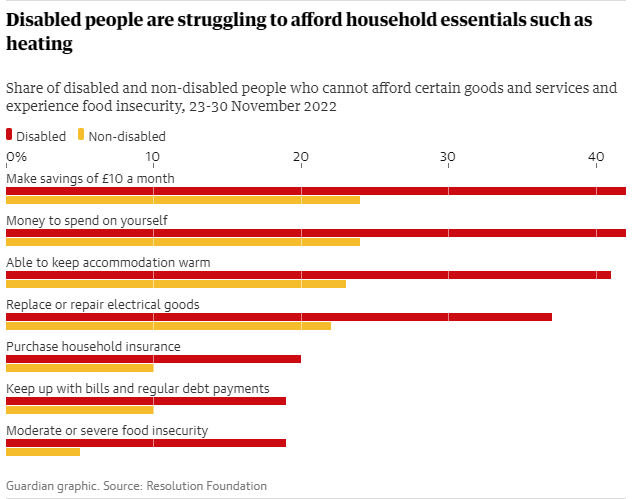

Massive gap in income causing further deprivation for the disabled

Research from the Resolution Foundation highlighting “massive” income gaps amid the cost of living squeeze” was reported by the Guardian in January 2023. According to the report, disabled people in the UK are much more likely to struggle to heat their homes and cut back on food during winter, It found people with disabilities had an available amount to spend that was 44% lower than that of other working-age adults, exposing them hugely to the rising cost of essentials.

It commented there was a chasm between the underlying disposable incomes of people with a disability (£19,397 a year) and the non-disabled population (£27,792), according to analysis of official figures and a YouGov survey of just under 8,000 working-age adults, more than 2,000 of whom reported a long-term illness or disability.

Highlighting the risks to households struggling with the highest rates of inflation since the early 1980s, it said almost half (48%) of disabled adults said they had to cut back on energy use, compared with almost one-third of people without a disability.

41% of people with a disability said they could not afford to keep their homes warm, compared with 23% of the non-disabled population. People with a disability are far more likely to be poorer than the rest of the population, with up to a third of adults in the lowest-income households having a disability, compared with fewer than a tenth of those in the richest homes.

The report found that the income gaps were only partly explained by lower employment rates among disabled workers. Even after accounting for employment status, more than half of the original income gap remains, showing that in-work disabled people face an increased risk of being on lower incomes than their peers.

After the government announced its plans for making cost of living support payments available generally the Resolution Foundation said further support measures would be needed to help disabled people, given the additional financial pressures faced amid the cost of living crisis.

Giant health assessment firms paid £millions but not meeting targets

Campaigning magazine Private Eye reported in January 2023 that a sample DWP audit found that a fifth of work capability assessments for Universal Credit and Employment and Support Allowance by Maximus-owned Centre for Health and Disability Assessments were found to be substandard with four out of every 100 judged “unacceptable”. For PIP it was worse. A third of all health assessments carried out by Atos and Capita are substandard with three out of every 100 “unacceptable”.

According to the government’s web site (see Section 3.4.9) “From 2016 onwards, providers’ targets will be: 3% or less ‘unacceptable’ reports; and a minimum of 85% of reports must be assessed as ‘acceptable’ or ‘acceptable: HP learning required’.” So, for the most part these (fairly weak or rather generous depending on your point of view) performance targets are not being met by these giant firms despite the £millions of tax payers’ money going into them.

Damaging effect of the 2022 rise in the cost of living

In March 2022 ITV News reported that families looking after those who are disabled were increasingly worried about being able to pay their bills as the cost of living soared. As essential services and goods like heating, travel, equipment and therapies became more expensive, families living with less and less were being forced to go without essential items.

In one instance a family saw their electricity bill rise from £1,800 a year to more than £5,000.

Tom Marsland, policy manager at the charity Scope, said: “Amid the worst cost of living crisis in decades, disabled people and their families are being left high and dry by the Government. Life costs more if you’re disabled, but the support being offered doesn’t touch the sides for disabled families. Spiralling living and energy costs are crushing disabled people who have already been cutting back for months. Many already face sky-high energy bills from needing more energy to charge vital equipment, or extra heating to stay warm.”

Flaws in the system lead to 80,000 PIP decisions being overturned at review

In an Independent article from February 2022 it explained how the Department of Work & Pensions had admitted it had wrongly refused disabled people benefits at record rate while the cost of needless reviews to taxpayers soared.

Campaigners pointed to “flaws in the system” that led to almost 80,000 Personal Independence Payment (PIP) decisions being overturned at initial review in 2021.

Meanwhile, separate figures show the cost of the reviews has surged by 26% in the prior two years, despite the fact that the number of reviews carried out by the DWP decreased by 23 per cent over the same period.

Claimants who wish to appeal a PIP decision, which are based on assessments by two private firms – Capita and Atos – must first appeal through the department’s internal process, known as mandatory reconsideration. The rate at which these appeals have led to a decision being reversed has surged from 22% (46,580 of 236,720) three years ago to 43% (78,390 of 182,880) in 2021, according to data obtained via a freedom of information request.

Separately, figures published by DWP minister Chloe Smith in response to a written parliamentary question show that the cost to taxpayers of mandatory considerations for PIP were £24.8m in 2021, compared with £19.7m in 2018/19 and £13.7m in 2016/17.

The disproportionate impact of the pandemic on the disabled

From the Office for National Statistics

In a survey carried out in July 2020 (figures for non-disabled in brackets where provided):

- 75% of disabled people said they were “very worried” or “somewhat worried” about the effect that the coronavirus was having on their life.

- 25% (13%) were most concerned about the impact on their well-being.

- 13% (3%) were most concerned about access to healthcare and treatment.

- 25% (7%) receiving medical care before the pandemic said they were currently receiving treatment for only some of their conditions.

- 45% of disabled people reported high anxiety.

- 46% (18%) say that the pandemic has worsened their mental health.

- 42% (29%) are feeling lonely.

- 36% (25%) say they spend too much time alone.

- 25% (8%) feel like a burden on others, or have no one to talk to about their worries.

- 40% (29%) had not met up with other people to socialise.

- 9% (3%) are feeling very unsafe when outside their home.

From Public Health England

People with learning disabilities were up to six times more likely to die from Covid-19 during the first wave of the pandemic, analysis shows. A report from Public Health England (PHE) found the death rate for those with a learning disability was 30 times higher in the 18-34 age group. Mencap said the government had “failed to protect” a group already experiencing health inequalities. Social Care Minister Helen Whately has announced a review of the findings. (Reported by the BBC 13 November 2020.)

Risk of death over three times greater for more severely disabled people

As reported in the Daily Mirror on 11 February 2021, disabled people made up 6 in 10 Covid deaths last year. Figures from the Office for National Statistics (ONS) shows that of the 50,888 deaths from January 24 2020 to 20 November 2020, 30,296 were disabled people – 59.5% whereas disabled people made up only 17.2% percent of the study population.

Richard Kramer, chief executive of Sense, quoted in the Independent said disabled people had been “largely forgotten” during the pandemic and that cuts in social care support affecting those living independently had left disabled people at greater risk.

ONS researchers said no single factor explains the considerably raised risk among disabled people – saying the type of residence, socio-economic and geographical circumstances, and pre-existing health conditions all play a part.

Mehrunisha Suleman, senior research fellow at the Health Foundation, said the latest figures showed current measures to protect disabled people “are not enough” and that there was “an urgent need for more and better support”. She said: “Disabled people are more likely to have one or more long-term health conditions, which means they are at greater risk of suffering severe symptoms if they get Covid-19. “However, as well as protecting disabled people from exposure to the virus, measures must account for the potential negative effects of lockdown and shielding.”

Being disabled in Britain – A journey less equal

The Equality and Human Rights Commission promotes and enforces the laws that protect our rights to fairness, dignity and respect. As part of its duties, the Commission provides Parliament and the nation with periodic reports on equality and human rights progress.

In ‘Being disabled in Britain: A journey less equal’ it assessed the state of equality and human rights for disabled people in Britain and set out the key areas requiring improvement. The overall picture emerging from the data is that disabled people are facing more barriers and falling further behind.

Poverty and social exclusion

The New Policy Institute in its report Monitoring Poverty and Social Exclusion 2016 found, “One aspect of poverty that can be understated in the official statistics is disability. When the extra costs of disability are partially accounted for, half of all people in poverty are either disabled, or in a household with a disabled person. Disability and family type are significant in explaining the children still in workless households; 46% of children in workless households have at least one disabled adult in the household.” Download the report summary below.

UN Convention on the Rights of Disabled People – Government Civil Society Shadow Report

This report was put together by Deaf and Disabled People’s Organisations led by Inclusion London and comments on how well the government is doing to implement the Convention. It references the laws and policies introduced since 2017 when the UK was last examined by the UN Disability Committee. The key findings were as follows:

• The situation for Disabled people has gotten worse.

• The government has taken some positive steps, but has not addressed key problems.

• The pandemic response discriminated against disabled people and violated their equal right to life.

• Disability, equality and human rights approaches towards disability have been further undermined.

Suicides linked to DWP benefit decisions

Cases where people claiming benefits died or came to serious harm have led to more than 150 government reviews since 2012, a BBC investigation found. An inquest on just one case concluded in January 2021 that authorities made 28 errors in managing her case. In another, a family received a letter endorsing the decision to stop benefits saying the claimant was fit to work while, in fact, she was lying in a mortuary ahead of her burial, her mother said.

Internal reviews are held by the DWP when it is alleged its actions had a negative impact, or when it is named at an inquest. However, it has been 11 years since the government was first made aware there was a problem with the tests it used to assess benefit claims after a coroner wrote to the DWP following the suicide of a man. During all that time, the government has simply marked its own homework, doing internal reviews.

Calling for an inquiry, Labour MP Debbie Abrahams who previously read out in the Commons the names of 29 people who have died, said: “There needs to be an independent inquiry investigating why these deaths are happening and the scale of the deaths needs to be properly understood.”

Secretary of State for Work and Pensions Thérèse Coffey told the Work and Pensions Committee in February 2021 the DWP “did not have a duty of care or statutory safeguarding duty”.

In October 2022, Disability News Service published a report on the way in which, after being granted £100m funding in 2019 to implement the DWP Excellence Plan, “a serious attempt to put right some of the worst parts of DWP processes which would have saved lives, misery and hardship for millions of disabled people”, the department took six different and deliberate actions to water down its effect. Among these was:

- abandoning plans to pilot a scheme – SignpostingPlus – that would have tested ways of supporting claimants who were “beginning to struggle to cope, before they become harder to help through entrenched disadvantage”. The DWP told DNS that it holds no information about SignpostingPlus, blaming the pandemic for the decision to abandon the project;

- the Plan also intended to “reduce the impact of serious cases (including customer suicide)” and measure how successful the department was in reducing the number of serious cases. But the department told DNS that it does not hold information about how successful it was in reducing serious cases because a “measure was not chosen”; and

- the plan also described how a new “Safeguarding Improvement Team” would “proactively introduce processes, procedures and policies to protect vulnerable customers and improve the effectiveness of DWP interventions”. But the department told DNS, three years on: “No information is held about a Team named the Safeguarding Improvement Team.”

Read our report here about the causal link between the disabled, financial hardship (particularly brought about by welfare benefits being stopped or reduced) and the likelihood of attempted suicide.

£443,500,000 spent on fighting disability claims

According to the Independent, tax payers fund more than £60million a year fighting disability claims even though on average three out of every four (or 100% in our case throughout 2020 and 2021) of cases that end up at a benefit tribunal are lost. Tick-box health assessments by giant outsourcing firms lead to many flawed decisions that mean the outlay by the Department for Work and Pensions is largely wasted. The impact on disabled people from forcing them to fight in the courts, however, can be devastating, pushing some into poverty and increasing levels of stress and anxiety.

The annual cost in 2020 was £60m but in 2018 it was £44m per annum and that 39% increase is far greater than the increase in applications which was 13% higher for the same period. Despite all this the outsourcing firms in 2020 had their lucrative multi-million pound contracts extended by a further two years to 2023.

This is all despite the DWP knowing that PIP claimants have the lowest level of benefit fraud. According to their own report Fraud and Error in the Benefit System (published 17/5/2018) fraud overpayments for the various benefits it controls are as follows: Housing benefit 4.6%, Employment and Support Allowance 2.2%, Pension Credit 3.5%, Jobseeker’s Allowance 4.3%, Universal Credit 4.7%, Personal Independence Payment 1.2%.

Research carried out by the charity Scope and reported by ITV News in April 2022 found that £200m of the total expenditure of £440m was spent resisting genuine cases, in which the initial rejection was later overturned. Altogether, more than 1.2 million decisions concerning Personal Independence Payments and Employment Support Allowance were found to be wrong between 2013 and 2021.

The figures came as two whistleblowers – who both worked as PIP assessors in 2016 and 2020 claimed the system was to blame, arguing it was “not designed to help disabled people but to try to block them from getting benefits”. Both said they were:

- ordered by managers to downgrade the points they wanted to award to claimants;

- told to mark disabled people down if they arrived at appointments well-kempt – with neatly brushed hair or clean-shaven; and

- asked to assess people with conditions for which they had little specialist knowledge.

Report: “Uses of Health and Disability Benefits” suppressed

Ministers refused to reveal this damning 80-page report for more than a year until a committee of MPs demanded it from the research firm that carried it out. It found some of the poorest claimants – those in low-paid jobs, with unmanageable debt, or out-of-work households whose only income came from the welfare system – “were often unable to meet essential day-to-day living needs, such as heating their house or buying food”. These poorer benefit claimants with children were sometimes led to “limit or stop spending on their health”.

Anastasia Berry of the MS Society said: “Despite the DWP’s relentless attempts to bury this research, we can finally see what they’ve been so desperate to hide. It has uncovered the inadequacy of these benefits for many disabled people. It shows some are struggling to pay for essential day-to-day expenses, such as food, heating and medications. The DWP’s failed cover-up of this damning research is just the latest example of their disregard for disabled people.

For years, disabled people have been subjected to a benefits system which is stressful, confusing, and fails to provide the basic support they need. Now, with the cost of living crisis erupting, many are reaching breaking point.”

Disabled people suffer a higher rate of domestic abuse

Disabled people experience higher rates of domestic abuse than non-disabled. In the year to March 2015 the Crime Survey for England and Wales reported that women and men with a long standing illness or disability were more than twice as likely to experience some form of domestic abuse than women and men with no long standing illness or disability. Research has found that disabled victims of domestic abuse also suffer more severe and frequent abuse over longer periods of time than non-disabled victims.

SafeLives’ data reveals that disabled victims typically endure abuse for an average of 3.3 years before accessing support, compared to 2.3 years for non-disabled victims. Even after receiving support, disabled victims were 8% more likely than non-disabled victims to continue to experience abuse. For one in five (20%) this ongoing abuse was physical and for 7% it was sexual.

For a disabled person, the abuse they experience is often directly linked to their impairments and perpetrated by the individuals they are most dependent on for care, such as intimate partners and family members. National data shows that disabled victims are much more likely to be suffering abuse from a current partner (31%) than non-disabled victims (18%).

Indices of deprivation

Many disabled people and their carers living in the communities we serve start off with a disadvantage compared to other areas of Suffolk and of England as a whole according to the Indices of Deprivation 2019 Report published by Public Health Suffolk. Download an extract here:

The Social Model

Read here about the Social Model of disability and compare it with the Medical Model to get a better perspective on disability and impairment and get an understanding of the difference between the two.